Students and faculty members came together over coffee and lunch to take part in discussion and discovery in the Middle East Studies Center on Thursday. Attendees were presented with a lecture about women authors in Iran and their trajectory through history from Dick Davis, a professor of Persian and chair of the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures at Ohio State University.

From Iran, women’s words sing

Students and faculty members came together over coffee and lunch to take part in discussion and discovery in the Middle East Studies Center on Thursday.

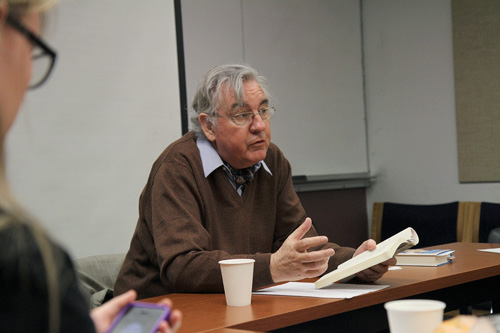

Attendees were presented with a lecture about women authors in Iran and their trajectory through history from Dick Davis, a professor of Persian and chair of the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures at Ohio State University.

Davis is an author, translator and editor. He has published more than 20 books and translations from Italian and Persian.

Davis’ lecture took the audience from the ninth century to today and discussed female writers who, in many cases, history has completely forgotten.

“Persian literature really begins in the ninth century,” Davis said. “All the people in the beginning were poets. Not to say there wasn’t prose. Most of [the writers] whom are remembered and revered are verse writers.”

One of the first prominent poets was Rabe’eh Qozdari.

“She was the first woman poet history is aware of,” Davis said. “Early poetry tends to be quite happy. Rabe’eh is the exception. That anger was unique…it is now a constant theme.”

Scholars do not know exactly when Qozdari wrote, but she did so from what is now Northern Afghanistan. She specialized in short poems that were filled with rage about injustice. Many of her poems have been lost to time.

“Jahan Malek Khatun is the only poet who lived in the medieval centuries whose complete manuscripts have come down to us,” Davis said.

Khatun’s poems were not widely released during her lifetime. The only published exposure she had was in death, when her works were briefly discussed in a biography. She was then virtually forgotten until 1955, when her poems were published and finally released.

“She is one of the greatest premodern poets,” Davis said. “Her love poems are very charming.”

Between that and the 14th century and the 19th century, women’s work faded, Davis said.

“It begins to revive again in the 19th century, partly because of outside influence. It shifts with Western influence,” he added.

Another influential poet was Alam Taj. “She’s one of the most interesting poets I know of, and she is virtually unknown,” Davis said.

Taj was known as a child prodigy of poetry, but she only published one poem in her lifetime. She entered into a marriage controlled by her husband, who forbade her from writing poetry. In one instance she was caught, and her works were burned. She was forced to write in secret and hid her poetry throughout her house. They weren’t found until her death. Because of this, her poems have been incredibly hard to come by, Davis said.

“Most people haven’t read her poems,” he said. “I had to have a friend Xerox me a copy of some of [them].”

In modern times, one of the most famous Iranian women authors is Fattaneh Haj Seyed Javadi. She’s an “extremely controversial writer, but not in the way you’d think,” Davis said.

Her book, the title of which roughly translates to The Morning After, has created much controversy among readers, he said. “Intellectuals in Iran hate it. Its message is extremely conservative.”

The book tells the tale of a woman who rebels against her wealthy family by marrying a poor carpenter. The story that follows explores her grief and heartbreak in the wake of her decision. It attacks cross-class marriage, and intellectuals are very opposed to that message, Davis said.

Most of the poems and stories Davis shared were long forgotten by history and are only now being made available to the public. Audiences can now read and appreciate the stories through new translations and publications.

The lecture, hosted by the Middle East Studies Center and the Millar Library, is part of a series titled Lunch & Learn.

“The Middle East Studies Center’s monthly brown-bag Lunch & Learn series provides an opportunity for the campus community to learn more about the Middle East through informal presentations and discussions with scholars and experts,” said Elisheva Cohen, outreach coordinator for the center. “These conversations provide a forum for the community to engage in thoughtful dialogue about the region, ask questions and share their opinions.”

The next lecture in the series is titled “The Arab Spring and Women’s Political Rights: Gain or Loss?” and will take place Thursday, March 7. The presentation will feature a lecture by Taghrid Khuri, adjunct faculty for the international studies and women’s studies programs at PSU.