One of the most widespread criticisms directed toward our national healthcare system—besides the accusation that it isn’t much of a national healthcare system because of its failure to cover a majority of America’s population—is that it is obsessed with profit at the expense of fulfilling the lapidary objective of helping people and extending life.

Some critics contend that a completely different system of healthcare is necessary. This system would do away with surgeries and medicine tested and proven to work via science, and instead rely on age-old treatments steeped in culture and misunderstanding. A common solution offered to the flaws of so-called Western medicine is Chinese medicine.

Living in Portland, we are exposed to a depressingly high number of schools like the National College of Natural Medicine and the Oregon College of Oriental Medicine, which claim to teach traditional Chinese medicine, or TCM, to practitioners and students.

At medical school fairs I have attended, the hawkers of TCM set up stands advertising the benefits of their practices right next to conventional medical schools. Given that Portland is a city that values offbeat thinking and lifestyles, it is unsurprising that it hosts an enormous number of believers in TCM relative to the rest of America.

“Believers” is the proper term to use for those who practice and use TCM, because the dichotomy between Western medicine and Chinese medicine is a false one. With scant hard evidence from scientific findings to back it up, TCM supporters depend on fallacious arguments concerning the “centuries of wisdom” and “enduring popularity” of their trade. They fail to realize that things such as astrology, the Mayan calendar or human and animal sacrifice, have had lasting prevalence which does not ensure that these ideas are just or correct.

I accidentally became a TCM patient several years ago in a pharmacy in Shanghai, and my experiences revealed that in terms of the pursuit of financial gain, TCM and Western medicine have a lot in common.

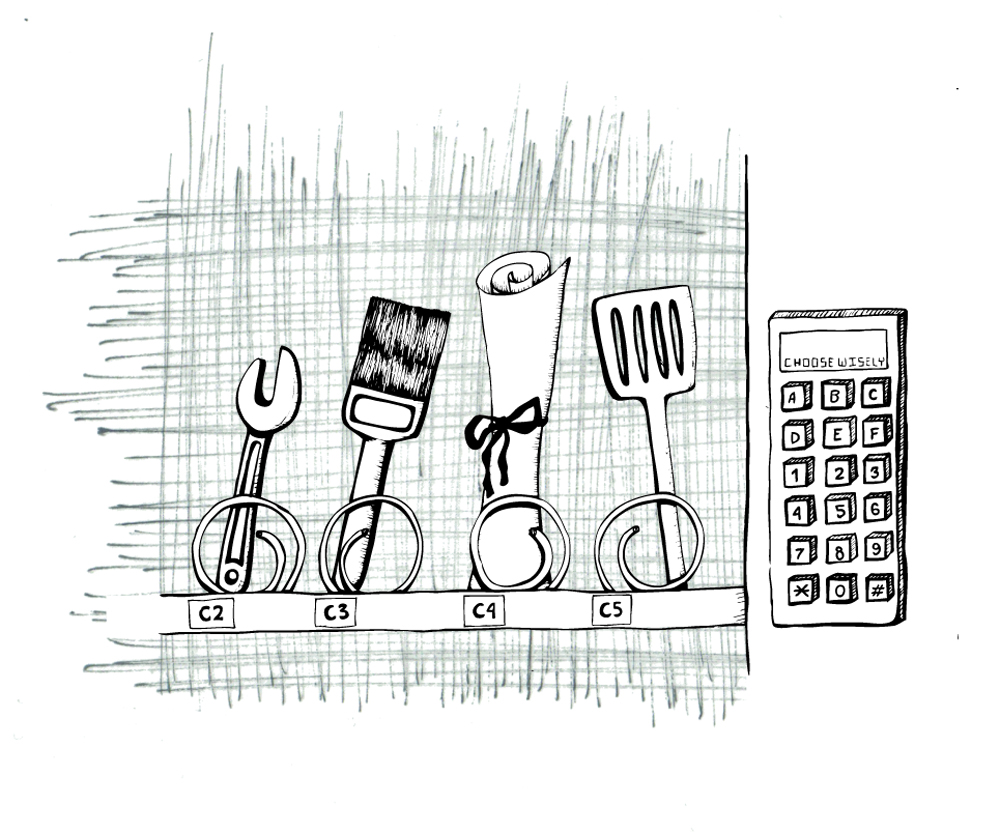

During an organized tour of southern China, we arrived at one branch of Tongrentang, which is a pharmaceutical chain store founded in 1669 that serves as the Chinese equivalent of Walgreens. Pharmacies are generally not interesting landmarks for tourists, and it soon was clear that we were brought in to hear a sales pitch. After an hour of hearing about products that cured everything from comas to constipation, we received free foot massages from store employees and were granted free consultations with a TCM doctor, who miraculously discovered that all of us present possessed dire health problems that could only be cured with thousands of dollars worth of Tongrentang products.

After spending several minutes taking my pulse and asking me about my diet and exercise, the doctor informed me that I was diagnosed with chronic diarrhea and stomach pains that I never even knew I had. My only hope was to purchase five boxes of herbs for the low price of $250 each. Examining my mother, the doctor concluded from her age that her life was made unbearable by the stress of raising a wayward son and suffering from hot flashes. There was nothing she could do to improve except make a beeline for the pharmacy counter and pick up more herbs worth $700.

“I’d really like to buy some, but we’re on a budget and we can only afford some of the medicine,” my mom replied.

“That’s all right,” the doctor responded without missing a beat. “You can both take the same medicine and recover.”

A miracle occurred that day. We discovered medicine that would not only stave off diarrhea and stomach cramps I never had, but would also alleviate symptoms of menopause. Soon enough, we heard the doctor note the success rate of the medicine in curing back pain, athlete’s foot and baldness. Terrified patients started reaching for their wallets to ward off diarrhea, menopause, back pain, athlete’s foot and baldness in one fell swoop.

Tongrentang operates across all of China, and even in other countries. It generates billions of yuan in profit each year, putting to rest the notion that Western medicine is only obsessed with money, while Chinese medicine lives in noble poverty.

Last fall, Slate published an incriminating article on TCM, noting inefficiencies and inconsistencies in its cures, the heavy promotion it received from Mao Zedong to become popular and undermine Western medicine and the heavy skepticism it receives even among native Chinese. I noticed baskets of dried beetles, bottles of preserved snakes in wine, and horns and tusks of deer, rhinos and elephants in display cases at Tongrentang. I wondered how many endangered species gave their lives to keep Tongrentang in business. Would environmentally conscious Portlanders still support TCM if they encountered the money-grubbers and peddlers of dead animals I met that day?

The popularity of TCM is a discouraging sign of humanity’s collective tendency to favor something obscure and unconventional simply because it is obscure and unconventional, no matter how much harm and deception is involved. As Portlanders, we take pride in bucking trends and popularizing ideas that few other people follow, be it fixed-gear bicycles, soccer, or cruelty-free vegan organic natural whole grain free-range clown beer. The flip side emerges when we reject fluoridation of water and use spurious arguments and data to convince people that simply because every other city fluoridates their water supply, we must remain different.

We find new thrills in adopting TCM and considering it to be just as legitimate as Western medicine, which means continuing to support a false dichotomy. There is no such thing as Western, allopathic, evidence-based, scientific or profit-based medicine, nor is there Chinese, aryuvedic, naturopathic or holistic medicine. The only division in medicine is between medicine that works and medicine that doesn’t work. TCM squarely fits in the latter category, and the sooner we accept this truth, the less harm we will do to fellow humans and other animals on Earth.